Project / Naga–The Serpent Spirit of Southeast Asia

Task / Research & Photo Documentation

Client / (William Harald-Wong—a self-initiated project)

Exhibitions / Samwon Paper Gallery, Seoul, South Korea / Fusion Art Institute, Shizuoka, Japan

Year / South Korea 2004, Japan 2008

All photographs by William Harald-Wong

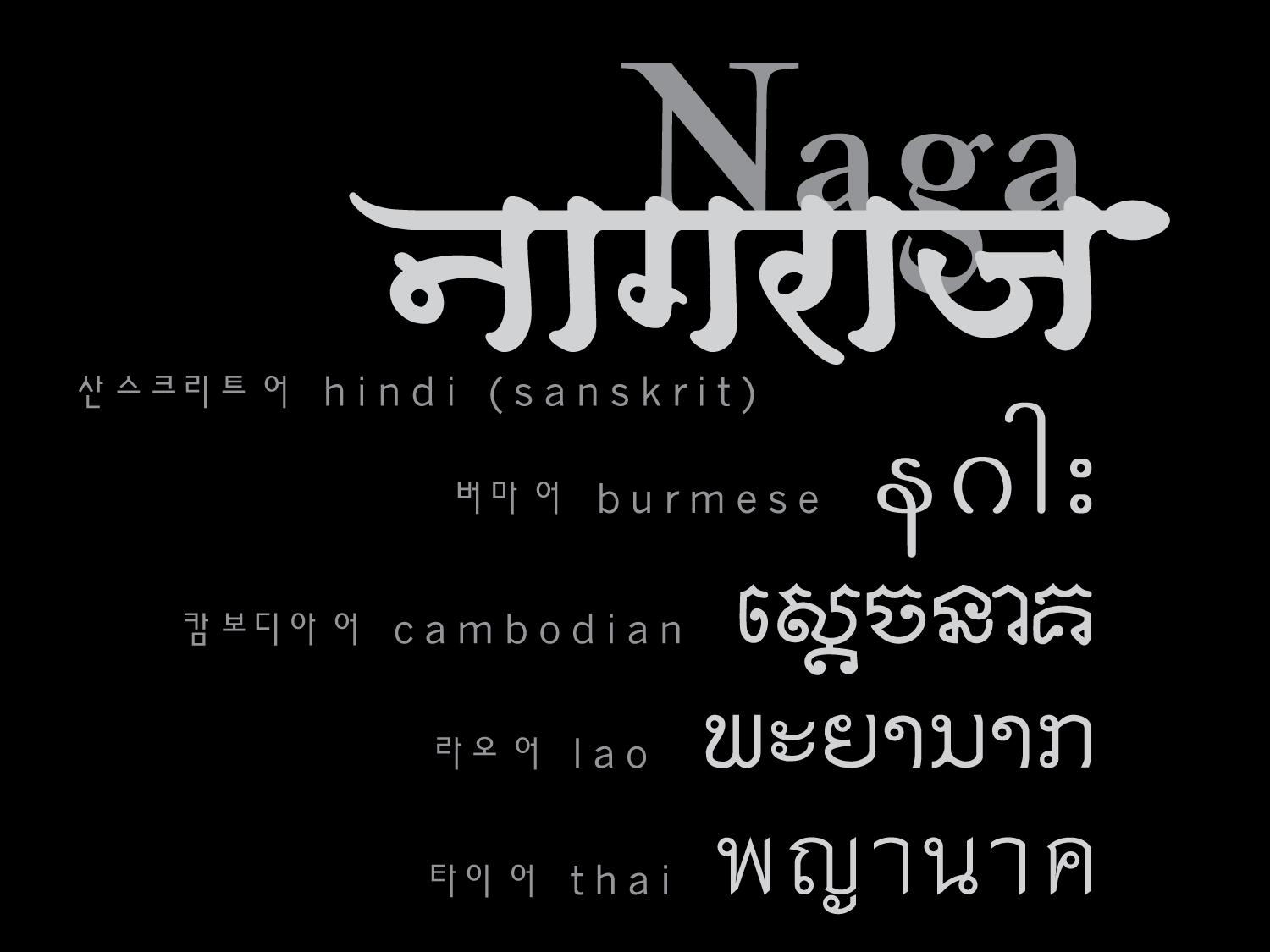

Naga, a Sanskrit word for serpent, refers to both living cobras as well as mythical ones. In ancient Buddhist texts, it may also mean an elephant (probably because of its snake-like trunk) or a mysterious person of nobility.

Naga is a personal project piqued by my curiosity to understand Southeast Asia’s deep connection with the serpent spirit and its relationship to the Chinese dragon.

I have been fortunate to be able to make many trips across Asia, either as an invited speaker, a judge for design competitions, on business, or a long-delayed vacation. Whatever the occasion, I had to sneak out between social engagements to do a bit of quiet photography.

Having to manage and lead a design company full time, I do not have the luxury of weeks on end to focus solely on this project. Hence, the collection of images that were exhibited in Seoul was pieced together over six years, covering Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, India, France and the Czech Republic—the two European countries provided me with their viewpoints on dragons and serpents.

I have excerpted some text and images from the Seoul exhibition here. You can download the full version at the end of this web page.

The Samwon Paper Gallery is a paper & printing resource centre and a cultural art space that hosts international exhibitions and lectures on topics related to the design industry.

Naga—The WATER SYMBOL of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, with its many rivers, islands and long coastal stretches, gave rise to several ‘water civilisations’—civilisations that flourished because of its location near a prominent water body. Almost every ethnic group in Southeast Asia believe that the creation of the world involved water, usually in the form of a flood that followed the cosmic fire.

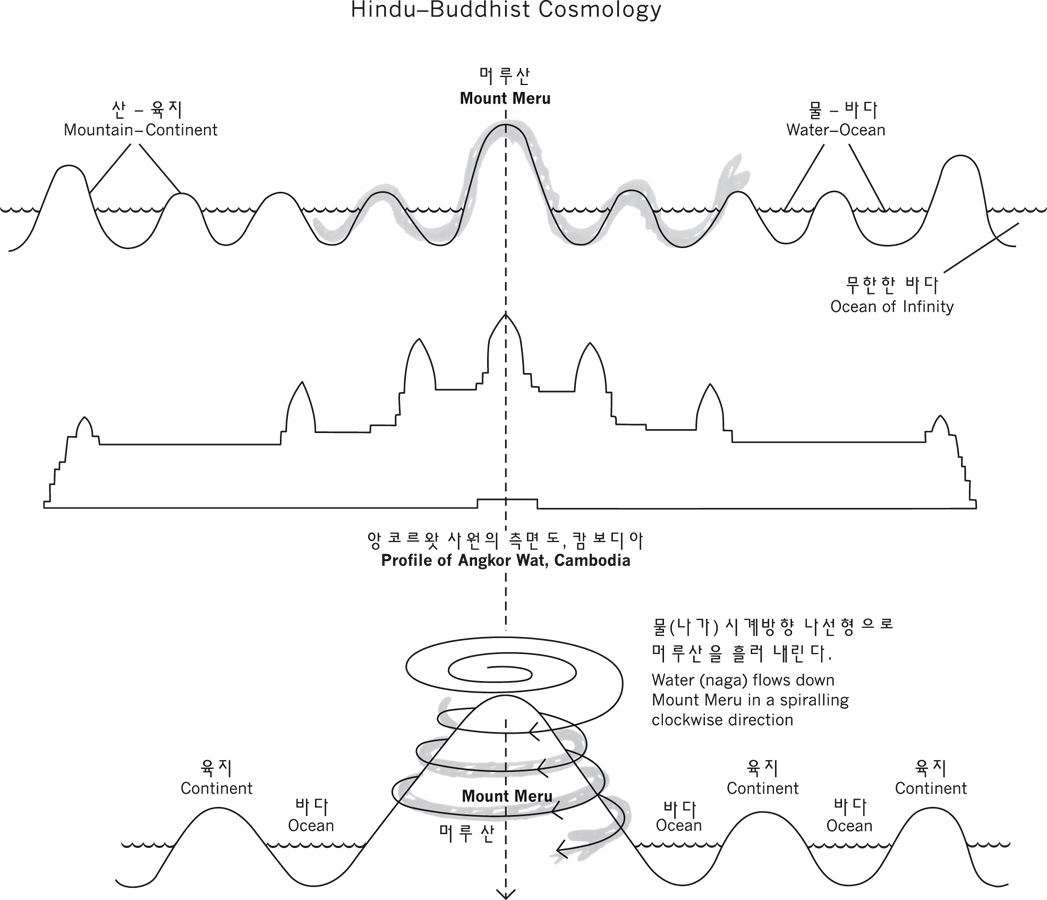

And as people regularly travel across waters, they also start to witness various water-related phenomena and develop beliefs based on their observations. The accumulated experience in the region with the sea alternating with the land could have led to the formulation (or adaptation) of the Hindu-Buddhist Cosmological Model, which has alternate rings of oceans and continents with the sacred Mount Meru in the centre.

Korean translation courtesy of Sanwon Gallery; The concept was expanded from an original work by Sumet Jumsai in his book, Naga–Cultural Origins in Siam and the West Pacific

The rippling profile of this series of concentric rings of oceans and continents resembles the slithering movement of the naga. People believe that the water flowing clockwise* down Mount Meru also represents the naga, as illustrated in murals and illuminated manuscripts.

Nagas are the guardians of the life energy stored in springs, wells and ponds—the water of the earth that is essential for a bountiful harvest. The fact that young cobras hatch during the monsoon season in many parts of Asia reinforces the naga’s role as a symbol of fertility and rebirth of the earth.

*Observation: I witnessed a traditional Chinese funeral wake in Malacca where the relatives of the deceased walked anti-clockwise around the coffin. An older man informed me that a clockwise movement represents the evolution of life, and an anti-clockwise action symbolises the draining away of the life force.

Rice-fields provide cover for deadly cobras where they hunt for rats but rarely attack the farmers. Photo: Mainland Penang, Malaysia

Naga—Male and Female; Yin and Yang

As a Male Symbol

The rearing, erect stance and spread hood of the cobra represent the male sex organ to villagers from India to Indonesia.

In Hindu temples, the cobra is considered a manifestation of Shiva, the god of destruction and creation. One finds in these Shiva temples the phallic linga set in the yoni, the female counterpart, often guarded by carved stone cobras.

The linga is comparable to Mount Meru. The waters of life flow down both and each has a receptacle at the base. In the case of the linga, it is the yoni, the female genitalia, where life takes form. The symbolism here is of fertility, which is both agricultural and human.

Because of this, fertility rites have included nagas since ancient times. During the annual festival of the snakes along India’s Malabar Coast in the 19th century, women encouraged living cobras to penetrate their vagina in a graphic simulation of the union between Shiva and his Energy, Shakti. These were religious rites considered essential for human welfare.

A Wayang Golok puppet. Puppets give visual form to the mythical forefathers of Javanese rulers who trace their ancestry to Hindu gods.

Photo: Jakarta, Indonesia

Linga-yoni in a family temple. The linga, according to the Skanda Purana (a Hindu religious text), symbolises the substance of the universe in the process of formation and dissolution.

Photo: Ghanerao, India

As a Female Symbol

Symbols in Asia have ancient roots from many sources, and they may have different meanings in different cultures.

It is a male symbol if we consider the shape, movement, and the fact that snakes live in holes in the ground. It is a female symbol if the snake, living in the earth, is regarded as a representative of Mother Earth. Also, serpents are often a great source of knowledge for particular plants, including sources of medicinal herbs and dyes for weaving. They are therefore closely linked with women and their traditional preoccupations.

Many temples have nagas as door guardians, often a male naga on one side and a female, complete with breasts, on the other. These pairs of nagas represent the yin and yang elements and therefore symbolise the dynamic balance between the couple.

Stone cobras at Buddha Park (Xieng Khuan), Vientiane. Live cobras grow up to eighteen feet long and are the world's largest poisonous snake. Death can come to a human within twenty minutes once bitten. Yet cobras have been raised to the status of life-giving gods, powerful symbols whose phallic shape and periodic shedding of the skin symbolise fertility, the seasonal rebirth of nature, and immortality. Photo: Vientiane, Laos

James McCarthy, the 19th Century English explorer, recounts the story of a mythical river-serpent of the Mekong River: “It is 53 ft long and 20 ins thick. When a man is drowned it snaps off the tuft of hair on the head, extracts the teeth, and sucks the blood; and when a body is found thus disfigured, it is known that the man has fallen victim to the nguak, or river serpent, at Luang Prabang.”

Photo: Vientiane, Laos

Naga_Hindu/Buddhist Beliefs

When Buddhism came to animist Southeast Asia 2,500 years ago, serpent worship was already well established. The wise Buddhist missionaries did not try to reject or replace the ancient snake cults but weaved the nagas into the stories of the Buddha instead, enabling them to win many converts.

Unlike Christianity, where the serpent was associated with the Devil, snakes were not perceived as evil in Southeast Asia and thus associating the nagas to the Buddha was not difficult.

The new narrative follows this line: All of nature’s creatures rejoice upon the appearance of the Buddha; and the serpent, as the guardian of the life-giving waters of the earth, is equally eager to serve and protect the Buddha.

The image of the seated Buddha protected by a mighty serpent with seven hoods is an archetypal image in Southeast Asian temple art. One finds a similar model in Hindu mythology whereby a naga guards the sleeping Hindu god Vishnu, thereby linking Hindu deities directly with Buddhism.

This relationship explains why it was easy to convert the ancient Hindu temples in Thailand and Cambodia to Buddhist temples.

St. George slaying the dragon. In Christianity, the serpent is often associated with the Devil, and the religion promoted the symbolism of saviour-versus-serpent. (Welsh folklore contains some notable exceptions to this view).

Photo: Prague, Czech Republic

Devotees purchase small squares of gold leaf as donations to the temple and rub the gold against the statue of Buddha, protected by the seven heads of the naga.

Photo: Bangkok, Thailand

Whether it's Hindu or Buddhist, nagas are found on lintels, form balustrades, and featured above every entryway in ancient temples throughout Thailand and Cambodia.

Photo: Sukhothai, Thailand

Naga and Garuda—Symbolical Antagonists

The Hindu deity Garuda is a giant golden bird, representing the heavens—the home of the stars, the sun, the moon, the gods, and the birds. He is the opposite of the earthbound nagas.

Garuda and Naga are an archetypical pair of symbolic antagonists: respectively, the champions of heaven and earth, day and night, open and closed, male and female.

The hot tropical sun of Garuda evaporates the earthy waters of Naga, but both Garuda’s light and warmth as well as Naga's soil and water are essential for growing crops. Many Southeast Asian (Hindu) gods have a dual nature—they create as well as destroy.

Garuda is famed for his supernatural powers, invulnerability (possesses mystic power against the effects of poison), and creative energy.

Photo: Rajasthan, India

Vishnu the Preserver, the best loved of all the Hindu gods, mounts Garuda—a common motif on the gables of Thai and Cambodian Buddhist monasteries.

Photo: Siem Reap, Cambodia

Bangkok’s Temple of the Emerald Buddha, the most revered shrine in Thailand, is kept “afloat” by a ring of golden garudas grasping nagas in their claws.

Photo: Bangkok, Thailand

Nagas, symbolising the water flowing down from Mount Meru, decorate the roofs of Lao wat (temples). In Thailand, this cho fa (architectural detail) can also feature a highly stylised garuda, the naga’s immortal enemy.

Photo: Vientiane, Laos

Naga in Daily Life

A vendor is selling milk ice-cream. The text reads ‘Blue Throat. Milk ice-cream depot; cashew pistachio, filled with almonds; 2, 3, 5, 7 rupees.’ “Blue Throat” is another name for Lord Shiva who turned blue because he consumed lethal poison, symbolised by the naga around his neck, to save the world.

Photo: Ajmer, India

A snake, an elephant (Ganesh) and Chinese food—quite an unappetising combination for outsiders—but food blessed with two prosperity symbols for those in the know.

The icon of a snake for this Chinese restaurant is not indicative of its menu but is a symbol for business prosperity. ‘Ganesh’ refers to the elephant-headed Hindu deity of Wisdom and Remover of Obstacles.

Photo: Mumbai, India

A tea stall in Chandni Chowk, Delhi. Shiva’s three aspects—as the god of truth, creative energy, and darkness (as destroyer)—make him a prominent figure in popular art, and his imagery pervades everyday life, thereby connecting earth life to a mythical one.

Photo: Delhi, India

NAGA MANIFESTATIONS

The cobra is considered a manifestation of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and creation. In the ancient religions of Indo-China, human sacrifice was essential to appease the Phi (Spirits) to ensure a good harvest and to guarantee the welfare of the community. Shiva fitted perfectly into this traditional pattern.

Photo: Batu Caves, Selangor, Malaysia

The gunungan (Tree of Life) is an intricately carved tree or leaf-shaped puppet that serves to open and close all shadow puppet performances. Symbolically, it represents the created world—with images of monkeys, birds, snakes, even insects—in which human beings live. The Maha Makara (a sea monster with scales and the trunk of an elephant) represents the presence of evil spirits; or on a microcosmic plane, the many negative emotions and desires that reside in the human heart.

Photo: Kelantan, Malaysia

Animals of the earth (nagas, elephants, dogs, etc.) made of flour protect blessing or healing rituals that invoke the spirits. Animals are intermediaries between the human world and heaven and can see and understand things, innate and subliminal, that humans cannot. The flour animal figures are floated away in a river after the ceremony.

Photo: Kelantan, Malaysia

In Bali, every man-microcosm is attended to by two nagas representing the physical needs of mortal man—safety, food, clothing and shelter—which are no longer needed after death. At the cremation ceremony, these nagas are symbolically killed by a flower-tipped arrow to symbolise the release of the spirit from its earthly physical needs and its sins.

Photo: Bali, Indonesia

A weathered advertising sign in Bangkok (without the text), possibly for a herbal medicine shop.

Photo: Bangkok, Thailand

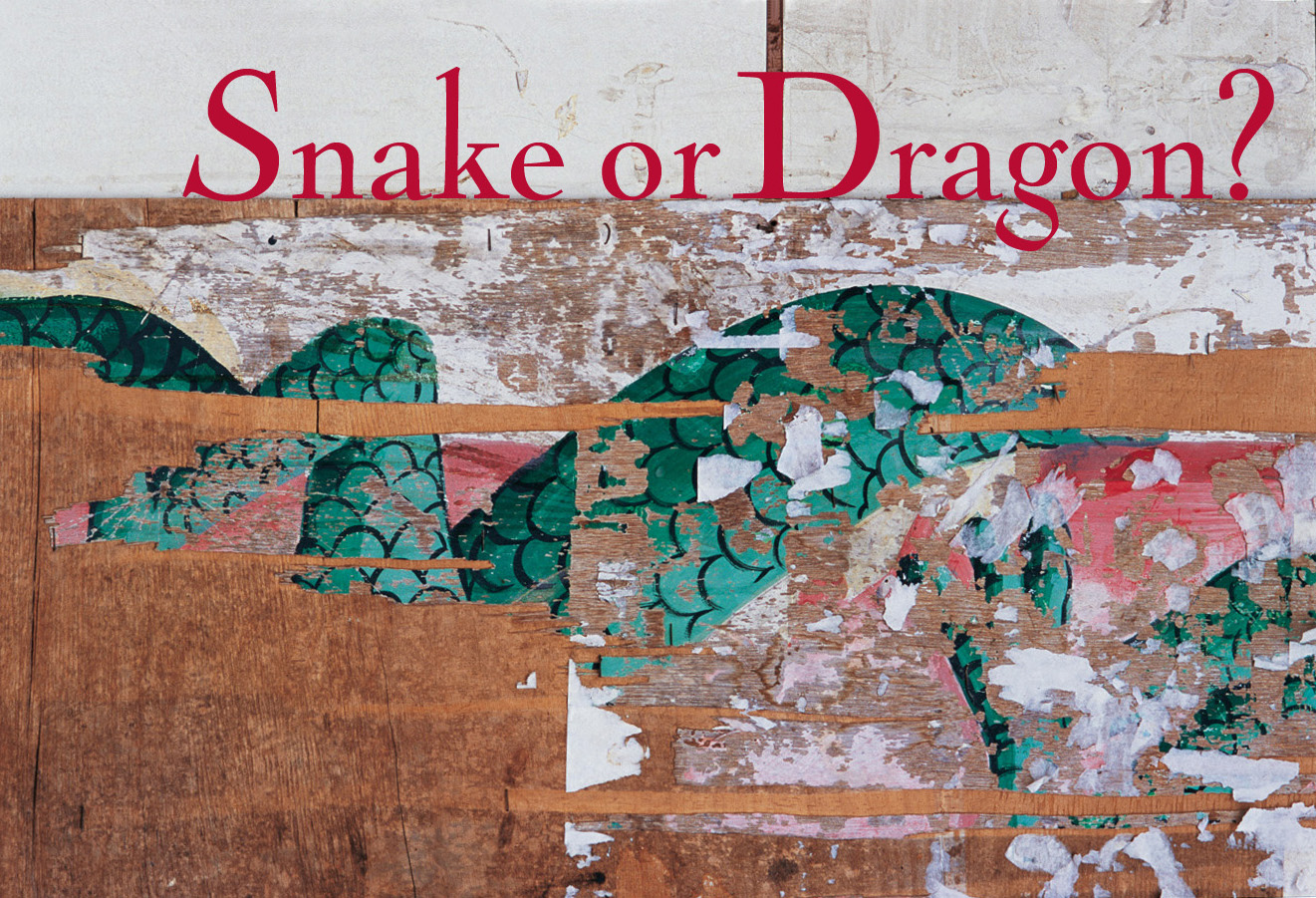

As one travels northward through Laos towards China, the snake-form of Southeast Asia seems to transmute (‘grows legs’) into the dragon-form of North Asia. The mid-way point is where the beliefs of the community change, having been influenced either by Southeast Asia/India or China.

Photo: Vientiane, Laos

ANCIENT THOUGHTS FOR MODERN PRACTICE

The naga has inspired several of my posters.

People have often asked me about the relevance of myths in today’s world. I believe it is about imagination—mythology is a fountain with an unending flow of exuberant ideas that inspires creativity. The enigmatic Thai film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives—directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul which won the 2010 Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or—explores a similar thought: the blending of myth and the supernatural with the everyday, the ordinary.

Add to that, an article by Fast Company, “How a Degree in Scandinavian Mythology can Land You a Job at one of the Biggest Tech Companies”.

The relevance of mythology in contemporary society is best summed up by M.L. West:

For the full article (in English and Korean), published in Asia Design Journal by the Korean Design Research Institute, please click on the image below.